Quick Guide: Interpreting Simple Linear Model Output in R

Linear regression models are a key part of the family of supervised learning models.

13 mins reading time

Linear regression models are a key part of the family of supervised learning models. In particular, linear regression models are a useful tool for predicting a quantitative response. For more details, check an article I’ve written on Simple Linear Regression - An example using R. In general, statistical softwares have different ways to show a model output. This quick guide will help the analyst who is starting with linear regression in R to understand what the model output looks like.

In the example below, we’ll use the cars dataset found in the datasets package in R (for more details on the package you can call: library(help = "datasets").

summary(cars)

## speed dist

## Min. : 4.0 Min. : 2.00

## 1st Qu.:12.0 1st Qu.: 26.00

## Median :15.0 Median : 36.00

## Mean :15.4 Mean : 42.98

## 3rd Qu.:19.0 3rd Qu.: 56.00

## Max. :25.0 Max. :120.00

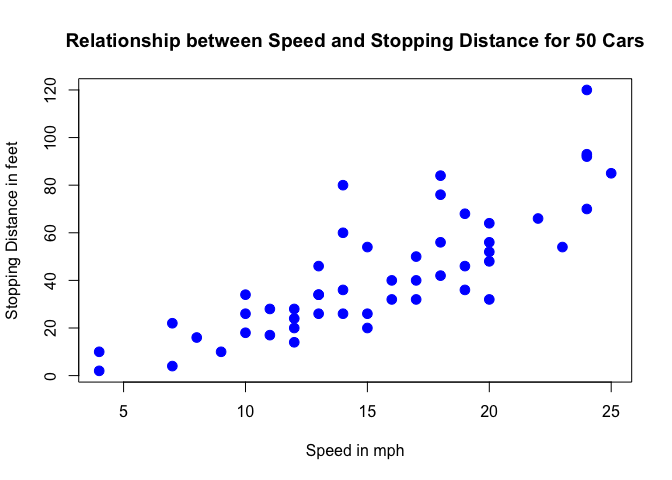

The cars dataset gives Speed and Stopping Distances of Cars. This dataset is a data frame with 50 rows and 2 variables. The rows refer to cars and the variables refer to speed (the numeric Speed in mph) and dist (the numeric stopping distance in ft.). As the summary output above shows, the cars dataset’s speed variable varies from cars with speed of 4 mph to 25 mph (the data source mentions these are based on cars from the ’20s! - to find out more about the dataset, you can type ?cars). When it comes to distance to stop, there are cars that can stop in 2 feet and cars that need 120 feet to come to a stop.

Below is a scatterplot of the variables:

plot(cars, col='blue', pch=20, cex=2, main="Relationship between Speed and Stopping Distance for 50 Cars",

xlab="Speed in mph", ylab="Stopping Distance in feet")

From the plot above, we can visualise that there is a somewhat strong relationship between a cars’ speed and the distance required for it to stop (i.e.: the faster the car goes the longer the distance it takes to come to a stop).

In this exercise, we will:

- Run a simple linear regression model in R and distil and interpret the key components of the R linear model output. Note that for this example we are not too concerned about actually fitting the best model but we are more interested in interpreting the model output - which would then allow us to potentially define next steps in the model building process.

Let’s get started by running one example:

set.seed(122)

speed.c = scale(cars$speed, center=TRUE, scale=FALSE)

mod1 = lm(formula = dist ~ speed.c, data = cars)

summary(mod1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = dist ~ speed.c, data = cars)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -29.069 -9.525 -2.272 9.215 43.201

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 42.9800 2.1750 19.761 < 2e-16 ***

## speed.c 3.9324 0.4155 9.464 1.49e-12 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 15.38 on 48 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.6511, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6438

## F-statistic: 89.57 on 1 and 48 DF, p-value: 1.49e-12

The model above is achieved by using the lm() function in R and the output is called using the summary() function on the model.

Below we define and briefly explain each component of the model output:

Formula Call

As you can see, the first item shown in the output is the formula R used to fit the data. Note the simplicity in the syntax: the formula just needs the predictor (speed) and the target/response variable (dist), together with the data being used (cars).

Residuals

The next item in the model output talks about the residuals. Residuals are essentially the difference between the actual observed response values (distance to stop dist in our case) and the response values that the model predicted. The Residuals section of the model output breaks it down into 5 summary points. When assessing how well the model fit the data, you should look for a symmetrical distribution across these points on the mean value zero (0). In our example, we can see that the distribution of the residuals do not appear to be strongly symmetrical. That means that the model predicts certain points that fall far away from the actual observed points. We could take this further consider plotting the residuals to see whether this normally distributed, etc. but will skip this for this example.

Coefficients

The next section in the model output talks about the coefficients of the model. Theoretically, in simple linear regression, the coefficients are two unknown constants that represent the intercept and slope terms in the linear model. If we wanted to predict the Distance required for a car to stop given its speed, we would get a training set and produce estimates of the coefficients to then use it in the model formula. Ultimately, the analyst wants to find an intercept and a slope such that the resulting fitted line is as close as possible to the 50 data points in our data set.

Coefficient - Estimate

The coefficient Estimate contains two rows; the first one is the intercept. The intercept, in our example, is essentially the expected value of the distance required for a car to stop when we consider the average speed of all cars in the dataset. In other words, it takes an average car in our dataset 42.98 feet to come to a stop. The second row in the Coefficients is the slope, or in our example, the effect speed has in distance required for a car to stop. The slope term in our model is saying that for every 1 mph increase in the speed of a car, the required distance to stop goes up by 3.9324088 feet.

Coefficient - Standard Error

The coefficient Standard Error measures the average amount that the coefficient estimates vary from the actual average value of our response variable. We’d ideally want a lower number relative to its coefficients. In our example, we’ve previously determined that for every 1 mph increase in the speed of a car, the required distance to stop goes up by 3.9324088 feet. The Standard Error can be used to compute an estimate of the expected difference in case we ran the model again and again. In other words, we can say that the required distance for a car to stop can vary by 0.4155128 feet. The Standard Errors can also be used to compute confidence intervals and to statistically test the hypothesis of the existence of a relationship between speed and distance required to stop.

Coefficient - t value

The coefficient t-value is a measure of how many standard deviations our coefficient estimate is far away from 0. We want it to be far away from zero as this would indicate we could reject the null hypothesis - that is, we could declare a relationship between speed and distance exist. In our example, the t-statistic values are relatively far away from zero and are large relative to the standard error, which could indicate a relationship exists. In general, t-values are also used to compute p-values.

Coefficient - Pr(>t)

The Pr(>t) acronym found in the model output relates to the probability of observing any value equal or larger than t. A small p-value indicates that it is unlikely we will observe a relationship between the predictor (speed) and response (dist) variables due to chance. Typically, a p-value of 5% or less is a good cut-off point. In our model example, the p-values are very close to zero. Note the ‘signif. Codes’ associated to each estimate. Three stars (or asterisks) represent a highly significant p-value. Consequently, a small p-value for the intercept and the slope indicates that we can reject the null hypothesis which allows us to conclude that there is a relationship between speed and distance.

Residual Standard Error

Residual Standard Error is measure of the quality of a linear regression fit. Theoretically, every linear model is assumed to contain an error term E. Due to the presence of this error term, we are not capable of perfectly predicting our response variable (dist) from the predictor (speed) one. The Residual Standard Error is the average amount that the response (dist) will deviate from the true regression line. In our example, the actual distance required to stop can deviate from the true regression line by approximately 15.3795867 feet, on average. In other words, given that the mean distance for all cars to stop is 42.98 and that the Residual Standard Error is 15.3795867, we can say that the percentage error is (any prediction would still be off by) 35.78%. It’s also worth noting that the Residual Standard Error was calculated with 48 degrees of freedom. Simplistically, degrees of freedom are the number of data points that went into the estimation of the parameters used after taking into account these parameters (restriction). In our case, we had 50 data points and two parameters (intercept and slope).

Multiple R-squared, Adjusted R-squared

The R-squared ($R^2$) statistic provides a measure of how well the model is fitting the actual data. It takes the form of a proportion of variance. $R^2$ is a measure of the linear relationship between our predictor variable (speed) and our response / target variable (dist). It always lies between 0 and 1 (i.e.: a number near 0 represents a regression that does not explain the variance in the response variable well and a number close to 1 does explain the observed variance in the response variable). In our example, the $R^2$ we get is 0.6510794. Or roughly 65% of the variance found in the response variable (dist) can be explained by the predictor variable (speed). Step back and think: If you were able to choose any metric to predict distance required for a car to stop, would speed be one and would it be an important one that could help explain how distance would vary based on speed? I guess it’s easy to see that the answer would almost certainly be a yes. That why we get a relatively strong $R^2$. Nevertheless, it’s hard to define what level of $R^2$ is appropriate to claim the model fits well. Essentially, it will vary with the application and the domain studied.

A side note: In multiple regression settings, the $R^2$ will always increase as more variables are included in the model. That’s why the adjusted $R^2$ is the preferred measure as it adjusts for the number of variables considered.

F-Statistic

F-statistic is a good indicator of whether there is a relationship between our predictor and the response variables. The further the F-statistic is from 1 the better it is. However, how much larger the F-statistic needs to be depends on both the number of data points and the number of predictors. Generally, when the number of data points is large, an F-statistic that is only a little bit larger than 1 is already sufficient to reject the null hypothesis (H0 : There is no relationship between speed and distance). The reverse is true as if the number of data points is small, a large F-statistic is required to be able to ascertain that there may be a relationship between predictor and response variables. In our example the F-statistic is 89.5671065 which is relatively larger than 1 given the size of our data.

Note that the model we ran above was just an example to illustrate how a linear model output looks like in R and how we can start to interpret its components. Obviously the model is not optimised. One way we could start to improve is by transforming our response variable (try running a new model with the response variable log-transformed mod2 = lm(formula = log(dist) ~ speed.c, data = cars) or a quadratic term and observe the differences encountered). We could also consider bringing in new variables, new transformation of variables and then subsequent variable selection, and comparing between different models. Finally, with a model that is fitting nicely, we could start to run predictive analytics to try to estimate distance required for a random car to stop given its speed.